The SHOTO Child Protection Policy is detailed in full below the form.

How To Raise A Concern

If you need to raise a concern, please contact our Child Protection Officer, Heather Mollison, using the form below, and she will get back to you as soon as possible.

Child Protection Policy

Children's Safeguarding Policy

- Document type: Policy.

- Version: 1.0.

- Author (name and designation): SHOTO Safeguarding Team:

- Child Protection Officer: Heather Mollison.

- Tony Kilcullen.

- Mike Trogal.

- Konomi Yajima.

- Dermot Lynch.

- Validated by: SHOTO Safeguarding Team.

- Date Validated: November 2020.

- Ratified by: SHOTO Council.

- Date Ratified: November 2020.

- Keywords: child safeguarding, child protection abuse, duty of care, CPSU, prevent, FGM, breast ironing, breast flattening, GDPR, DBS checks, photographic filming, incident reporting.

- Date uploaded to internet: November 2020.

- Review date: June 2021.

Version Control

| Version | Type of change | Date | Revisions from previous issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | New document | November 2020 | Not applicable. |

| Major revisions | None. |

Introduction

Throughout this document the Shotokan Traditional Karate Organisation is referred to as SHOTO. SHOTO has developed this policy for implementation throughout the SHOTO association and its member clubs, based on the EKF’s Child Safeguarding Policy.

SHOTO fully recognises the need to make optimal provision for the safeguarding and wellbeing of children and young persons, that participate in the sport of karate, either as a self-defence art or sport environment, and acknowledges its moral and legal responsibility to ensure that:

- The welfare of the child is paramount

- All children, whatever their age, culture, disability, gender, language, racial origin religious beliefs and/or sexual identity have the right to protection from abuse.

- All suspicions and allegations of abuse will be taken seriously and responded to swiftly and appropriately

- All instructors and volunteers (paid or unpaid) working within our organisation have a responsibility to report concerns to the appropriate child protection officer

The Children’s Act 1989 defines a child as a person under the age of 18. SHOTO recognises this in this policy.

SHOTO is committed to working in partnership with all agencies to ensure best practice when working with children and young people within our organisation and member clubs.

Adopting best practice will help to safeguard those participants from potential abuse as well as protecting instructors, volunteers and other adults in positions of responsibility from any potential allegation of abuse.

This document is binding and provides procedures and guidance to everyone within SHOTO, whether working in a voluntary or professional capacity.

Policy Statement

SHOTO has a duty of care to safeguard all children being taught in karate by SHOTO instructors (and volunteers) from harm.

All children have a right to protection, and the needs of disabled children and others who may be particularly vulnerable must be taken into account. As such SHOTO will strive to ensure the safety and protection of all children involved in our sport through adherence to the EKF’s Children’s Safeguarding Policy.

The policy is applicable to all within SHOTO.

Sport can and does have a very powerful and positive influence on people - especially young people. Not only can it provide opportunities for enjoyment and achievement, but it can help to develop and enhance valuable qualities such as self-esteem, leadership and teamwork. SHOTO must ensure that for those positive experiences to be realised, the sport is delivered by people who have the welfare of young people uppermost in their mind and that SHOTO must have robust systems and processes in place to support and empower them.

Policy Aims

The aim of this policy is to promote good practice:

- Providing children and young persons with appropriate safety and protection whilst in the care of clubs and instructors affiliated to SHOTO.

- Ensure that all incidents of poor practice and allegations of abuse will be taken seriously and responded to swiftly and appropriately.

- Allow all instructors /volunteers to make informed and confident responses to specific child protection issues.

- The policy recognises and builds on the legal and statutory definition of a child.

- The distinction between ages of consent, civil and criminal liability are recognised but in the pursuit of good in the delivery and management of SHOTO, a young person is recognised as being under the age of 18 years [Children’s Act 1989].

- SHOTO recognises that persons above the age of 18 are vulnerable to undue influence by adults in positions of responsibility and this policy also therefore applies to vulnerable adults.

- SHOTO will provide a suitably experienced and qualified individual to act as their Child Protection Officer and commit to a series of awareness raising and training seminars and workshops to assist them in fulfilling their role.

- Confidentiality will be upheld in line with the Data Protection Act 1984 and the Human Rights Act 2000.

- SHOTO will conduct annual reviews to ensure consideration of any EKF policy changes.

Promoting Good Practice

Child abuse, particularly sexual abuse, can arouse strong emotions in those facing such a situation. It is important to understand these feelings and not allow them to interfere with a judgement about the appropriate action to take.

Abuse can occur within many situations including the home, school and the sporting environment. It is a fact of life that some individuals will actively seek employment or voluntary work with young people in order to harm them. An, instructor, teacher, official or volunteer may have regular contact with young people and be an important link in identifying cases where a young person needs protection. All cases of poor practice should be reported to the designated CPO Heather Mollison following the guidelines in this document. When a child enters the club having experienced abuse outside the sporting environment, sport can play a crucial role in improving the child’s self-esteem. In such instances the club must work with the appropriate agencies to ensure the child receives the required support.

Good Practice Guidelines

All those involved in Martial Arts should be encouraged to demonstrate exemplary behaviour in order to safeguard children and young people and protect themselves from false allegations. The following are common sense examples of how to create a positive culture and climate within Martial Arts:

Good practice means:

- Always working in an open environment (e.g. avoiding private or unobserved situations and encouraging open communication).

- Treating all young people/disabled adults equally, and with respect and dignity.

- Placing the welfare and safety of the child or young person first above the development of performance or competition.

- Maintaining a safe and appropriate distance (e.g. it is not appropriate to have an intimate relationship with a child or to share a room with them).

- Building balanced relationships based on mutual trust, which empowers children to share in the decision-making process.

- Making sport fun, enjoyable and promoting fair play.

- Where any form of manual or physical support is required, it should be provided openly and in accordance with this policy document.

- Keeping up to date with the technical skills, qualifications and insurance within Karate.

- Involving parents/carers wherever possible (e.g. for the responsibility of their children in the changing rooms). If groups have to be supervised in the changing rooms, always ensure parents/teachers/instructors/officials work in pairs.

- Ensuring when mixed teams are taken away, they should always be accompanied by male and female instructors (NB however, same gender abuse can also occur).

- Ensuring that at tournaments or residential events, adults should not enter children’s rooms or invite children into their rooms.

- Being an excellent role model – this includes not smoking or drinking alcohol in the company of young people.

- Giving enthusiastic and constructive feedback rather than negative criticism.

- Recognising the developmental needs and capacity of young people and disabled adults – avoiding excessive training or competition and not pushing them against their will.

- Securing parental consent in writing to act in loco parentis, if the need arises to give permission for the administration of emergency first aid.

- Keeping a written record of any injury that occurs, along with the details of any treatment given.

- Requesting written parental consent if club officials are required to transport young people in their cars.

SHOTO’s Instructors need to understand the added responsibilities of teaching children and also basic principles of growth and development through childhood to adolescence. Exercises should be appropriate to age and build. Instructors should not simply treat children as small adults, with small adult bodies.

- There is no minimum age for a child beginning karate, insurance policy requirements notwithstanding, as the build and maturity of individuals varies so much. However, the nature of the class must be tailored to consider these factors.

- In general, the younger the child, the shorter the attention span. One hour is generally considered sufficient training time for the average 12-year-old or below. Pre-adolescent children have a metabolism that is not naturally suited to generating anaerobic power, and therefore they exercise better aerobically, that is, at a steadily maintained rate. However, they can soon become conditioned to tolerate exercise in the short explosive bursts that more suit Karate training.

- Children should not do assisted stretching - they generally don’t need to, and there is a real risk of damage with an inconsiderate or over-enthusiastic partner.

- Children should be carefully matched for size and weight for sparring practice.

- Great care must be taken, especially where children train in the proximity of adults, to avoid collision injury.

- Children should not do certain conditioning exercises; especially those, which are heavy, load bearing, for example weight training or knuckle push-ups. Children should not do any heavy or impact work but should concentrate on the development of speed, mobility, skill and general fitness.

- No head contact is permitted for children participating in kumite or partner work due to significant, evidenced based health concerns surrounding the impacts of concussion.

Practices To Be Avoided

The following should be avoided except in emergencies. If cases arise where these situations are unavoidable, they should only occur with the full knowledge and consent of someone in charge in the club or the child’s parents. For example, a child sustains an injury and needs to go to hospital, or a parent fails to arrive to pick a child up at the end of a session.

- Avoid spending excessive amounts of time alone with children away from others.

- Avoid taking children to your home where they will be alone with you.

The following should never be sanctioned. You should never:

- Engage in rough, physical or sexually provocative games, including horseplay.

- Share a room with a child.

- Allow or engage in any form of inappropriate touching.

- Allow children to use inappropriate language unchallenged.

- Make sexually suggestive comments to a child, even in fun.

- Reduce a child to tears with intent, as a form of control.

- Allow allegations made by a child to go unchallenged, unrecorded or not acted upon.

- Do things of a personal nature for children or disabled adults that they can do for themselves.

- Invite or allow children to stay with you at your home unsupervised.

NB. It may sometimes be necessary for instructors or volunteers to do things of a personal nature for children, e.g. if they are young or are disabled. These tasks should only be carried out with the full understanding and consent of parents and the student. If a person is fully dependent on you, talk with him/her about what you are doing and give choices where possible. This is particularly so if you are involved in any dressing or undressing of outer clothing, or where there is physical contact, lifting/assisting to carry out particular activities. Avoid taking on the responsibility for tasks for which you are not appropriately trained.

Incidents That Must Be Reported / Recorded

If any of the following occur you should report this immediately to another colleague and record the incident. You should also ensure the parents of the child are told if:

- You accidentally hurt a child or young person.

- He/she seems distressed in any manner.

- A student appears to be sexually aroused by your actions.

- A child or young person misunderstands or misinterprets something you have done.

Here are some practical ways in which you should help safeguard children and young people who take part in Karate training within SHOTO:

- Instructor/volunteer Ratios.

- Changing room awareness.

- Dealing with injuries and Illness.

- Collection of children by Parents/carers.

- Discipline issues.

- Physical contact issues.

- Sexual Activity issues.

- Participants with disabilities.

Defining Child Abuse

Child abuse is when an adult harms a child or young person. There are four main type of abuse:

- Physical abuse: This includes being hit, kicked, shaken or punched, or given harmful drugs or alcohol.

- Emotional abuse: This includes being called names, being threatened or being shouted at or made to feel small. Bullying is also a form of emotional abuse. Bullying includes hitting or threatening a child with violence, taking their things, calling them names or insulting them, making them do things they won't want to do, and deliberately humiliating or ignoring them. Cyber-bullying is also included in this category.

- Sexual abuse: This includes being touched inappropriately by an adult or young person, being forced to have sex, or being made to look at sexual pictures or videos. For some disabled children, it includes if a person helping them to use the toilet touched them more than was needed.

- Neglect: Is when a child is not looked after properly, including having no place to stay, or not enough food to eat, or clothes to keep them warm. It also includes if the child is not given medical care when they need it, including medication. For some disabled children, it could include if their carer took away the things they needed for everyday life - like their wheelchair or communication board. Or not helping a disabled child who needed help using the toilet.

Common Signs Of Abuse

Every child is unique, so behavioural signs of abuse will vary from child to child. In addition, the impact of abuse is likely to be influenced by the child's age, the nature and extent of the abuse, and the help and support the child receives. However, there are some behaviours that are commonly seen in children and young people who have been abused:

- The child appears distrustful of a particular adult, or a parent or an instructor/volunteer with whom you would expect there to be a close relationship.

- He or she has unexplained injuries such as bruising, bites or burns - particularly if these are on a part of the body where you would not expect.

- If he or she has an injury which is not explained satisfactorily or properly treated.

- Deterioration in his or her physical appearance or a rapid weight gain or loss.

- Pains, itching, bruising, or bleeding in or near the genital area.

A change in the child's general behaviour. For example, they may:

- Become unusually quiet and withdrawn, or unexpectedly aggressive. Such changes can be sudden or gradual.

- If he or she refuses to remove clothing for normal activities or wants to keep covered up in warm weather.

- If he or she shows inappropriate sexual awareness or behaviour for their age.

- Some disabled children may not be able to communicate verbally about abuse that they may be experiencing or have witnessed. It is therefore important to observe these children for signs other than 'telling'.

These signs should be seen as a possible indication of abuse and not as a confirmation. Changes in a child’s behaviour can be the result of a wide range of factors. Visible signs such as bruising or other injuries cannot be taken as proof of abuse. For example, some disabled children may show extreme changes in behaviour, or be more accident prone, as a result of their impairment. A child or young person may also try to tell a person directly about abuse. It is very important to listen carefully and respond sensitively. SHOTO has a responsibility to act on any concerns.

Children With Additional Needs

SHOTO recognise that children with either a physical or mental disability are more prone to being abused than other children. Children with a disability are more likely to be abused as a consequence of the following:

- Vulnerabilities to bullying from other children and adults.

- Likely to be more socially isolated and have less frequent contact than children without disabilities.

- Dependency on others for assistance in order to carry out essential daily tasks.

- The inability or a difficulty in expressing themselves and communicating that abuse has taken place.

- Impaired capacity to resist and understand abuse.

It is the responsibility of all to ensure that the duty of care to children is upheld at all times and in order to bring about the most inclusive environment for disabled children there are areas of good practice which will need to be taken into consideration. These include:

- Disabled access to dojos, competition, transport and accommodation.

- Adapting instructing practices to suit the needs of the child.

- Improving ways of communication including where relevant sign language and other appropriate means of communication dependent upon the needs of the child.

- Increased supervision at training and events.

- Appropriate changing, showering and toilet facilities for disabled children to be easily accessible.

- Instructors to have further training where required to understand the individual needs of the child.

- Opportunities for club or competition information to be made available in alternative means where necessary e.g. braille.

Whilst extra safeguards need to be afforded to protecting disabled children from abuse this does not mean that disabled children cannot play a full and active part in karate classes and competitions. Further advice is available from the EKF.

Children From Ethnic Minority Backgrounds

SHOTO’s Constitution ensures that discrimination is not permitted in any form. Discrimination is however more common with children from ethnic minority backgrounds. Therefore, due regard is needed when running or taking part in classes, competitions or other events, for cultural and language differences.

Children from ethnic minority backgrounds are also more susceptible to being abused for the following reasons:

- Language difficulties may make it difficult for the child to tell somebody that they are being abused.

- Children may be more socially isolated and have less contact with people from outside their community.

- Stereotyping or prejudice may lead to situations where abuse is not detected or is misinterpreted.

- Children may be more prone to being victims of discrimination and bullying.

In order to ensure that children from ethnic minority backgrounds are adequately safeguarded religious festivals and/or daily practices should be considered. For example, a child who is fasting during the festival of Ramadan may be more physically exhausted than usual and therefore due consideration ought to be given when training.

Moreover, to be as inclusive as possible it is advised that events – where possible – are not held on days which coincide with significant religious or cultural feast days. Some religions and cultures may also adhere to strict dietary requirements and therefore when planning things like team meals or catering for presentation nights for example, these dietary requirements should be taken into consideration e.g. vegetarian, halal, kosher.

Whilst it is not be manageable or proportionate for all clubs to ensure that they have information readily available in appropriate formats and languages for those clubs with a high proportion of ethnic minority students, consideration should be given to how to diversify the dissemination of information.

Radicalisation And Extremism

The government defines extremism as vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. Some children are at risk of being radicalised (adopting beliefs and engaging in activities which are harmful, dangerous or criminal) and instructors should remain alert to this risk.

Whilst any radicalisation signs may differ greatly from one child to another (with children also known to hide their views) this policy does not require SHOTO officials, instructors or clubs to undertake intrusive interventions into family life but to take action when potentially concerning behaviour has been identified.

There is no obligation or expectation that SHOTO or its members will take on a surveillance or enforcement role; rather any concerns should be flagged to the relevant Child Protection Lead for each region. The Child Protection Lead will then liaise with partner organisation in order to contribute to the prevention of terrorism and making safety a shared endeavour.

See Prevent Reporting Procedures flow chart – Appendix 1.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

FGM is the practice of intentionally removing part or all of the external female genitalia and/or other female genital organ injury for non-medical purposes with FGM having no health benefits. FGM may also be referred to as ‘female circumcision’ or ‘cutting’ and in diverse communities cultural references may be used which may be include; tahur, halalays, gudniin, sunna or khitan to name but a few.

The practice is a cultural one with no religious text requiring that girls are ‘cut’. It is most prevalent in African and Middle Eastern regions but it is not exclusively geographically defined. The countries with the highest prevalence of the practice include Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Nigeria and Somalia. The practice is also carried out in Asian countries such as Malaysia and has been known to occur in South America. Whilst these countries have the highest prevalence of the practice, it is carried out on a British citizen when parents take their child abroad.

There is no one way of undertaking the ‘cut’ and it can be carried out at a number of differing stages from two days after birth to before puberty or even during pregnancy. The age group which is most commonly affected ranges from 0-15 years.

This is an inhumane treatment which has been outlawed in the UK through the FGM Act 2003 and anybody who has been found guilty of the offence can face up to 14 years in jail. Additionally, anybody found to be failing in their duty of care and assumed responsibility e.g. a parent, who allows the practice to happen to their daughter can face up to 7 years in prison. The practice results in severe bleeding and problems during urination as well as infections, child- birth complications and the increased chance of infant mortality not to mention psychological problems.

Given these procedures are not fully irreversible, prevention is key. SHOTO and Associations have a duty of care to the children they come into contact with and if signs and symptoms are identified it is imperative that action is taken to either to bring about justice.

Key signs and symptoms to be mindful of:

- The child’s relatives are known to have had FGM.

- The family belongs to a community which is known to practice FGM.

- Cultural appropriations are not sufficient grounds for concern and accusations based solely upon cultural heritage should be discouraged. However, when taking into account other factors this may be a genuine cause for concern.

- The child will be absent from training for a number of weeks as they are planning on making a trip to one of the countries previously identified.

- Note this of itself is not a cause of concern and should be taken into consideration with other factors.

- You are involved in discussions with the child who discloses that they have a forthcoming special celebration.

- You notice that the child has difficulty either walking or sitting. The child may also be unable to carry out certain karate techniques or stretching/warm up exercises as they once did.

For further advice and guidance on FGM there is a free online course offered by the Home Office on FGM. This can be accessed by following the link: https://www.virtual-college.co.uk/resources/free-courses/recognising-and-preventing-fgm

Breast Flattening/Ironing

The terms breast flattening and breast ironing are used to refer to the procedure whereby young pubescent girls’ breasts are – over a period of time, including years – flattened and/or pounded down. The purpose of this is to delay the development of breasts entirely or to make the breasts permanently disappear.

The practice is usually done within families (often by female relatives) and involves large stones, hammers or spatulas being heated up over scorching hot coals to compress breast tissue. Other methods adopted can include the use of a binder or elastic belt to press the breasts.

It is something which usually starts when the girl first shows signs of puberty and can be as young as 9 years old.

Breast ironing and flattening may also be done by the child themselves as they may be undergoing gender transformation/identity issues.

Based upon research carried out by the National FGM Centre in the UK, it was found that the practice is largely confined to the African continent or those with African heritage with Cameroon being identified as one of the areas where this is most prevalent. Other countries known to carry out the procedure include Benin, Chad, Kenya, South Africa, Togo and Zimbabwe.

The health implications of such a practice, both physical and mental, can be extremely damaging with abscesses, severe fever and infections common- place.

Unlike FGM, there is no specific law which addresses the issue but it falls un- der the category of physical abuse and should be dealt with as such. How- ever, like FGM, the processes and procedures to follow if you identify or have suspicions that the practice has taken place are the same.

Signs and symptoms to look out for:

Signs and symptoms should be treated with caution and used in conjunction with other known facts or other signs and symptoms. For example, a girl may be embarrassed about her body for other reasons such as body confidence and is of itself not indicative that abuse has occurred. These signs may be noticed during karate sessions when a girl is changing before or after practice or when discussing with fellow students before, during or after sessions.

The main signs to look out for include:

- A girl being embarrassed about their body.

- A girl is born to a woman who has undergone breast flattening or members of the girl’s immediate family have.

- References to breast flattening in conversation.

- The girl’s family have limited levels of integration within the wider community.

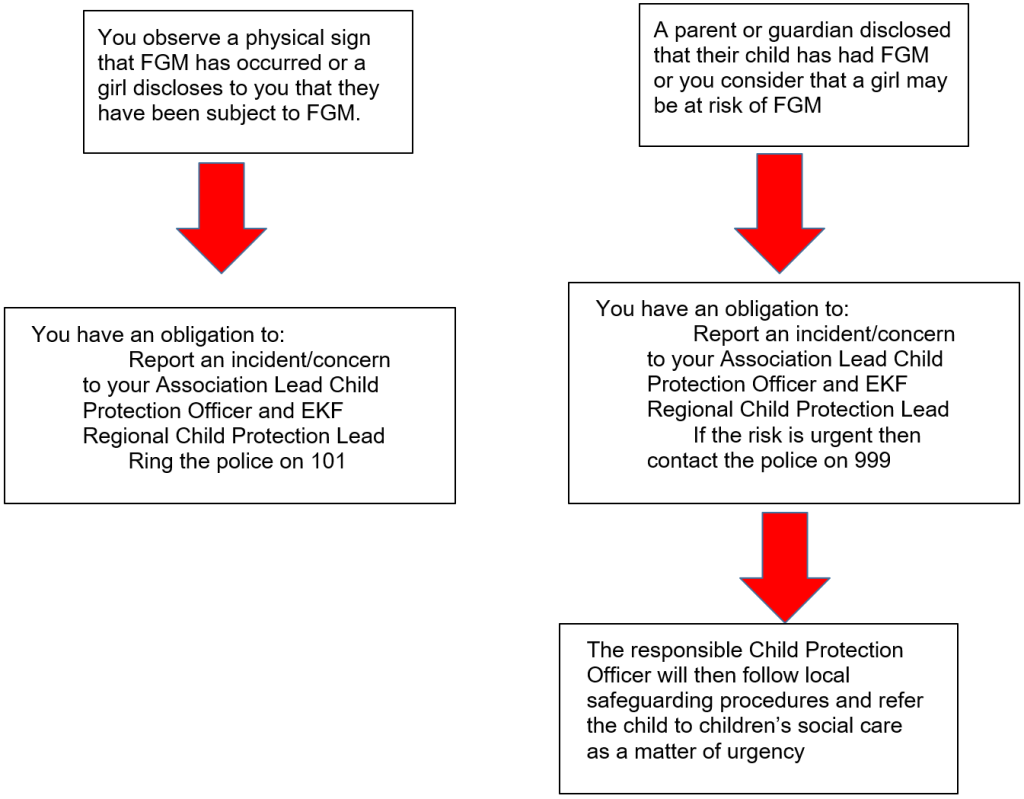

See FGM Reporting Procedures flow chart – Appendix 2.

Peer on Peer Abuse

Peer on Peer Abuse Children can abuse other children. This is generally referred to as peer on peer abuse and can take many forms. This can include, but is not limited to, bullying (including cyberbullying); sexual violence and sexual harassment; upskirting; physical abuse such as hitting, kicking, shaking, biting, hair pulling, or otherwise causing physical harm; sexting/youth produced sexual imagery and initiating/hazing type violence and rituals.

So Called ‘Honour Based’ Abuse (HBA)

So Called ‘Honour Based’ Abuse (HBA): encompasses crimes which have been committed to protect or defend the honour of the family and/or the community, including Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), forced marriage, and practices such as breast ironing. It can include multiple perpetrators. FGM comprises all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs. All forms of HBA are abuse (regardless of the motivation) and should be handled and escalated as such.

Upskirting

Upskirting: The Voyeurism (Offences) Act, which is commonly known as the Upskirting Act, came into force on 12 April 2019. ‘Upskirting’ is where someone takes a picture under a person's clothing (not necessarily a skirt) without their permission and or knowledge, with the intention of viewing their genitals or buttocks (with or without underwear) to obtain sexual gratification, or cause the victim humiliation, distress or alarm. It is a criminal offence. Anyone of any gender, can be a victim.

Responding To Suspicions Or Allegations

It is not the responsibility of anyone working in SHOTO, in a paid or unpaid capacity to decide whether or not child abuse has taken place. This is the role of the child protection agencies. However, there is a responsibility for all involved to act on any concerns through contact with the appropriate authorities. Advice and information are available from the local Social Services Department, The Police or the NSPCC 24-hour Help line 0808 800 5000.

SHOTO assures all instructors/volunteers that it will fully support and protect anyone, who in good faith reports his or her concern that a colleague is, or may be, abusing a child. Where there is a complaint against an instructor or volunteer there may be three types of investigation:

- A criminal investigation.

- A child protection investigation.

- A disciplinary or misconduct investigation.

The results of the Police and child protection investigation may well influence the disciplinary investigation, but not necessarily. Action Concerns about poor practice:

- If, following consideration, the allegation is clearly about poor practice, the Child Protection Officer will deal with it as a misconduct issue.

- If the allegation is about poor practice by the Child Protection Officer, or if the matter has been handled inadequately and concerns remain, it should be reported to the relevant officer who will decide how to deal with the allegation and whether or not to initiate disciplinary proceedings.

Concerns about suspected abuse:

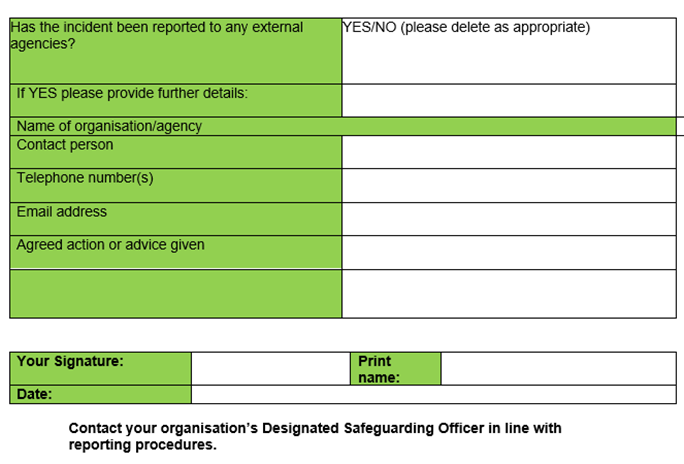

Any suspicion that a child has been abused by either an instructor or a volunteer should be reported to the Child Protection Officer, who will take such steps as considered necessary to ensure the safety of the child in question and any other child who may be at risk. See Incident Form Reporting Appendix 3, and concerns and welfare flow charts – Appendices 4 and 5.

The Child Protection Officer will refer the allegation to the social services department, which may involve the Police, or go directly to the Police if out-of-hours.

The parents or carers of the child will be contacted as soon as possible following advice from the social services department.

The Child Protection Officer should also notify the SHOTO Chair and Deputy Chair.

If the Child Protection Officer is the subject of the suspicion/allegation, the report must also be made to the Chair and Deputy Chair who will refer the allegation to social services.

Confidentiality

Every effort should be made to ensure that confidentiality is maintained for all concerned. Information should be handled and disseminated on a need to know basis only. This includes the following people:

- The Child Protection Officer.

- The parents of the person who is alleged to have been abused.

- The person making the allegation.

- Social services/police.

- SHOTO Chairman, Deputy Chairman and any disciplinary team set up via SHOTO’s Constitution.

- The alleged abuser (and parents if the alleged abuser is a child).

- Seek social services advice on who should approach the alleged abuser.

- Information should be stored in a secure place with limited access to designated people, in line with data protection laws (e.g. that information is accurate, regularly updated, relevant and secure).

Internal Inquiries And Suspension

All internal inquiries relating to Safeguarding will be overseen by the Child Protection Officer of SHOTO. Suspension(s) will be addressed in accordance with SHOTO’s Constitution.

The welfare of the child should remain of paramount importance throughout.

Support To Deal With The Aftermath Of Abuse

Consideration should be given to the kind of support that children, parents and instructors/volunteers may need. Use of helplines, support groups and open meetings will maintain an open culture and help the healing process.

The British Association for Counselling Directory is available from The British Association for Counselling, 1 Regent Place, Rugby CV21 2PJ, Tel: 01788 550899, Fax: 01788 562189, Email: bac@bacp.co.uk, Internet: https://www.bacp.co.uk

Consideration should also be given to what kind of support may be appropriate for the alleged perpetrator.

Allegations Of Previous Abuse

Allegations of abuse may be made some time after the event (e.g. by an adult who was abused as a child or by an instructor or volunteer who is still currently working with children). Where such an allegation is made, the club should follow the procedures as detailed above and report the matter to the social services or the police. This is because other children, either within or outside sport, may be at risk from this person. Anyone who has a previous criminal conviction for offences related to abuse is automatically excluded from working with children. This is reinforced by the details of the Protection of Children Act 1999.

Action If Bullying Is Suspected

If bullying is suspected, the same procedure should be followed as set out in 'Responding to suspicions or allegations' above.

Action to help the victim and prevent bullying:

- Take all signs of bullying very seriously.

- Encourage all children to speak and share their concerns (It is believed that up to 12 children per year commit suicide as a result of bullying, so if anyone talks about or threatens suicide, seek professional help immediately). Help the victim to speak out and tell the person in charge or someone in authority.

- Investigate all allegations and take action to ensure the victim is safe. Speak with the victim and the bully (ies) separately.

- Reassure the victim that you can be trusted and will help them, although you cannot promise to tell no one else.

- Keep records of what is said (what happened, by whom, when).

- Report any concerns to the Child Protection Officer or the school (wherever the bullying is occurring).

Action towards the bully (ies):

Talk with the bully (ies), explain the situation, and try to get the bully(ies) to understand the consequences of their behaviour. Seek an apology to the victim(s).

- Inform the bully (ies)’s parents.

- Insist on the return of 'borrowed' items and that the bully (ies) compensate the victim.

- Impose sanctions as necessary.

- Encourage and support the bully (ies) to change behaviour.

- Hold meetings with the families to report on progress.

- Inform all organisation members of action taken.

- Keep a written record of action taken.

Concerns outside the immediate sporting environment (e.g. a parent or carer):

- Report your concerns to the Child Protection Officer, who should contact social services or the police as soon as possible.

- See below for the information social services or the police will need.

- If the Child Protection Officer is not available, the person being told of or discovering the abuse should contact social services or the police immediately.

- Social services and the Child Protection Officer will decide how to involve the parents/carers.

- The Child Protection Officer should also report the incident to SHOTO Council.

- Maintain confidentiality on a need to know basis only.

Information For Social Services Or The Police About Suspected Abuse

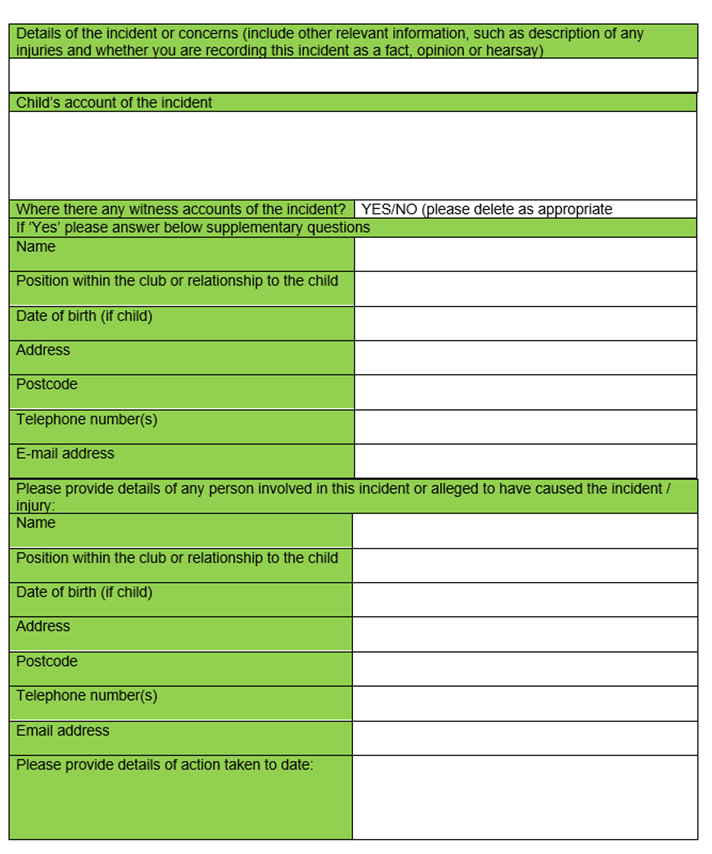

To ensure that this information is as helpful as possible, a detailed record should always be made at the time of the disclosure/concern, which should include the following:

- The child's name, age and date of birth of the child.

- The child's home address and telephone number.

- Whether or not the person making the report is expressing their own concerns or those of someone else.

- The nature of the allegation. Include dates, times, any special factors and other relevant information.

- Make a clear distinction between what is fact, opinion or hearsay.

- A description of any visible bruising or other injuries. Also, any indirect signs, such as behavioural changes.

- Details of witnesses to the incidents.

- The child’s account, if it can be given, of what has happened and how any bruising or other injuries occurred.

- Have the parents been contacted?

- If so, what has been said?

- Has anyone else been consulted? If so, record details.

- If the child was not the person who reported the incident, has the child been spoken to? If so, what was said?

- Has anyone been alleged to be the abuser? Record details.

- Where possible referral to the police or social services should be confirmed in writing within 24 hours and the name of the contact who took the referral should be recorded.

- If you are worried about sharing concerns about abuse with a senior colleague, you can contact social services or the police directly, or the NSPCC Child Protection Helpline on 0808 800 5000, or Childline on 0800 1111.

False allegations of abuse do occur, but they are rare. You should always take immediate action if a child says or indicates that he or she is being abused, or you have reason to suspect that this is the case. This may involve dealing with the child, his parent or carer, colleagues at your club / organisation, teachers, external agencies or the media. Children who are being abused will only tell people they trust and with whom they feel safe. As an instructor you will often share a close relationship with students and may therefore be the sort of person in whom a child might place their trust.

Children want the abuse to stop. By listening and taking what a child is telling you seriously, you will already be helping to protect them. It is useful to think in advance about how you might respond to this situation in such a way as to avoid putting yourself at risk.

Timing and Location:

It is understandable that the child may want to see you alone, away from others. The child may therefore approach you at the end of a session when everyone is going home, or may arrive deliberately early at a time when they think you will not be busy. However, a disclosure is not just a quick chat; it will take time and usually has further consequences. Bear in mind that you may also need to attend to other students / children, check equipment or set up an activity – you cannot simply leave a session unattended. Therefore, try to arrange to speak to the child at an appropriate time. Location is very important. Although it is important to respect the child’s need for privacy, you also need to protect yourself against potential allegations. Do not listen to the child’s disclosure in a completely private place – try to ensure that other instructors/volunteers are present or at least nearby.

All records should:

- Be written as soon as possible signed and dated.

- Clearly distinguish between fact, observation, allegation and opinion.

- Note the name, date, the event, a record of what was said, and any action taken in cases of suspected abuse.

- Be held separately from main records.

- Be exempt from open access.

Responding To The Child

- Do not panic – react calmly so as not to frighten the child.

- Acknowledge that what the child is doing is doing is difficult, but that they are right to confide in you.

- Reassure the child that they are not to blame.

- Make sure that, from the outset, you can understand what the child is saying.

- Be honest straight away and tell the child you cannot make promises that you will not be able to keep.

- Do not promise that you keep the conversation secret. Explain that you will need to involve other people and that you will need to write things down.

- Listen to and believe the child; take them seriously.

- Do not allow your shock or distaste to show.

- Keep any questions to a minimum but do clarify any facts or words that you do not understand – do not speculate or make assumptions.

- Avoid closed questions (i.e. questions which invite yes or no answers).

- Do not probe for more information than is offered.

- Encourage the child, to use its own words.

- Do not make negative comments about the alleged abuser.

- End the disclosure and ensure that the child is either being collected or is capable of going home alone.

- Do not approach the alleged abuser.

Safeguarding And Overnight Trips For Training Or Competitions

SHOTO and its instructors will not undertake training / national competitions with their respective clubs involving stays overnight.

Use Of Photographic Filming Equipment

There is no intention to stop people photographing their children, club mates, or photography and video being used as an educational tool, but this is in the context of appropriate safeguards being in place. There is evidence that some people have used sporting events as an opportunity to take inappropriate photographs or film footage of young and disabled sportspeople in vulnerable positions.

It is advisable that all clubs be vigilant with any concerns to be reported to the club Child Protection Officer.

Any parent who wishes to photograph their child must seek permission from the instructor.

Instructors must seek parental consent for photographs to be taken or published (e.g., on websites, social media).

Ensure students are appropriately dressed.

Encourage students to report if they are worried about any photographs that are taken of them.

A parental Consent form for the photography of children and young persons can be found in Appendix 7.

Videoing As An Instructing Aid

See previous section.

Recruitment And Training Of Staff And Volunteers – Applies To EKF Only

This section applies to EKF only.

EKF’s Expectation Of Affiliated Members

It is EKF Safeguarding Team and Board decision that all affiliated member associations will comply with the requirements laid out below by December 2019. Help and support to achieve this is available from the EKF Safeguarding Team and any club who fails to meet these criteria but is seen to be actively working towards the required criterion will not be sanctioned. However, active refusal to engage with the below may lead to SHOTO membership being rescinded.

Associations will need to comply with the following:

- Have a Lead Child Protection Officer for the Association (please see Appendix 6 for Job Description).

- The named person should have their contact details displayed on the official association website (e-mail address and telephone number).

- Lead to attend official Child Protection/Safeguarding training every 3 years provided by the EKF.

- Ensure association instructors and volunteers are compliant with DBS requirements by keeping and monitoring accurate records.

- Have a clear Child Safeguarding policy document in line with the Safeguarding Code in Martial Arts.

- The policy should include clear systems and processes for how concerns are received, processed and managed.

- For advice and guidance on how to proceed with cases that arise please contact your local EKF Child Protection Officer who will assist.

- The policy must make reference to the EKF Safeguarding Team and how to refer a concern accordingly. This may be particularly pertinent if the Lead Child Protection Officer is the subject of an accusation or complaint or the individual wishes the process to be managed outside of the association.

- The policy should include clear systems and processes for how concerns are received, processed and managed.

- Have a safeguarding referral form displayed on the website.

GDPR

Data and therefore the EU General Data Protection Rules 2018 and the ac- companying UK Data Protection Act 2018 (hereinafter GDPR and DPA respectively) will apply. SHOTO therefore has a requirement to process, store and share data accordingly.

A significant element of GDPR is informing people why an organisation wishes to collect for what purpose. Therefore, when SHOTO asks for DBS checks of instructors or volunteers, the reasons for collecting this data should be made clear to those being asked to provide evidence. By being open and honest about what data is being stored and what the purpose of storing this data is therefore provides an opportunity for informed consent. This allows people to make a decision as to accept or decline providing data. One of the key purposes of GDPR is to enhance the rights of an individual to restrict the processing of their data.

GDPR accountability is not solely directed at one person however the ac- countability rests with anyone who is collecting, managing and/or storing information. Crucially, this rule is applicable not just to data controllers (person charged with overall responsibility of the management of data) but also to data processors. Data processors can be volunteers, instructors or external parties which includes a website host or data storage company.

Within a children specific context, there are extra protections which need to be applied when processing and managing data. This will usually involve parental or guardian consent but additionally, any data capturing statements produced for children should be easy to understand with simple language used where possible.

Furthermore, any personal data which is gathered should be used for the primary purpose only, unless further consent has been granted from the persons in question for supplementary purposes. This includes any transferring of the data to another party. Any failure to obtain consent for a secondary purpose will constitute a breach of GDPR.

Further information on GDPR and how it affects EKF practices can be found by accessing the dedicated Information Governance Policy through the EKF/SHOTO website.

However, data which is gathered which is of a sensitive nature is different.

In order to process data without following the explicit consent processes previously mentioned, it is imperative that SHOTO is able to clearly articulate which lawful basis – as documented under Article 6 of GDPR regulations- is being applied especially when sharing confidential data with other agencies following accusations of child abuse in all its manifestations. Information of this nature should only be shared between appropriate agencies and should conform to Article 5(1) which includes the following requirements:

- Data should be relevant and have a rational link to the purpose.

- Limited to the pertinent details of the accusation (not all information held about said individual).

- Be adequate and sufficient in order to fulfil the purpose of sharing information.

- Only be shared with those who need all or some of the information (as reiterated in Caldicott Principles).

- Have a specific need to be shared at the time.

Under Articles 13 and 14 of GDPR which documents the individual’s right to be informed of what data is being collected and for what purpose. Genuine consent puts the individual in charge and helps build collaborative professional relationships. However, after having risk assessed a victim of abuse and deemed them to be at risk of serious harm or homicide then SHOTO is duty bound by existing legislation to share this information and no individual consent is required. If as required by UK law (DPA) data will be processed regardless of consent then asking for consent is both misleading and inherently unfair.

Similarly, Article 6(f) also documents legitimate interests as a lawful basis for processing data without informed consent. When relying on legitimate interests for the sharing of information this but be balanced against the interests and fundamental rights of the child involved. In summary, when dealing with accusations of abuse, there are justifiable moral and legal reasons why SHOTO will share the data with other appropriate agencies.

Documented below is a detailed breakdown of the lawful basis and legal grounds for sharing information with specific emphasis on those which would apply to SHOTO Safeguarding team:

- Article 6(c) Legal obligation: the processing is necessary for you to comply with the law (not including contractual obligations).

- Article 6(d) Vital interests: the processing is necessary to protect someone’s life.

- Article 6(e) Public task: the processing is necessary for you to perform a task in the public interest or for your official functions, and the task or function has a clear basis in law.

- Article 6(f) Legitimate interests: the processing is necessary for your legitimate interests or the legitimate interests of a third party unless there is a good reason to protect the individual’s personal data which overrides those legitimate interests. (This cannot apply if you are a public authority processing data to perform your official tasks.)

The main grounds in UK legislation for the requirement to share information with specific emphasis on Child Safeguarding include:

- Child protection. Disclosure to Children’s Social Care or the Police: Children Act 1989 and 2004.

- Prevention of abuse and neglect: The Care Act 2014.

- For the administration of justice – bringing perpetrators of crimes to justice: Part 3 and Schedule 8 of the Data Protection Act 2018.

- Prevention and detection of crimes: Section 115 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

- Right to life: Articles 2 and 3 of the Human Rights Act.

- Protection of the vital interests of the data subject e.g. prevention of serious harm (psychological, physical or sexual): Schedule 8 of the Data Protection Act 2018.

- Prevention of acts of terrorism or joining banned Organisations: Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015.

For further advice and guidance on GDPR and its implications for safeguarding and its use within sporting organisations, please refer to the Information Commissioners Office.

Monitoring Compliance And Review

There are circumstances in which the policy will be reviewed every year in order to maintain alignment with EKF Policy.

Appendix 1 - Prevent Reporting Flowchart

Escalation and Referral Process for Preventing Radicalisation of Children and Young People.

Appendix 2 - FGM Reporting Flowchart

You have concerns regarding FGM.

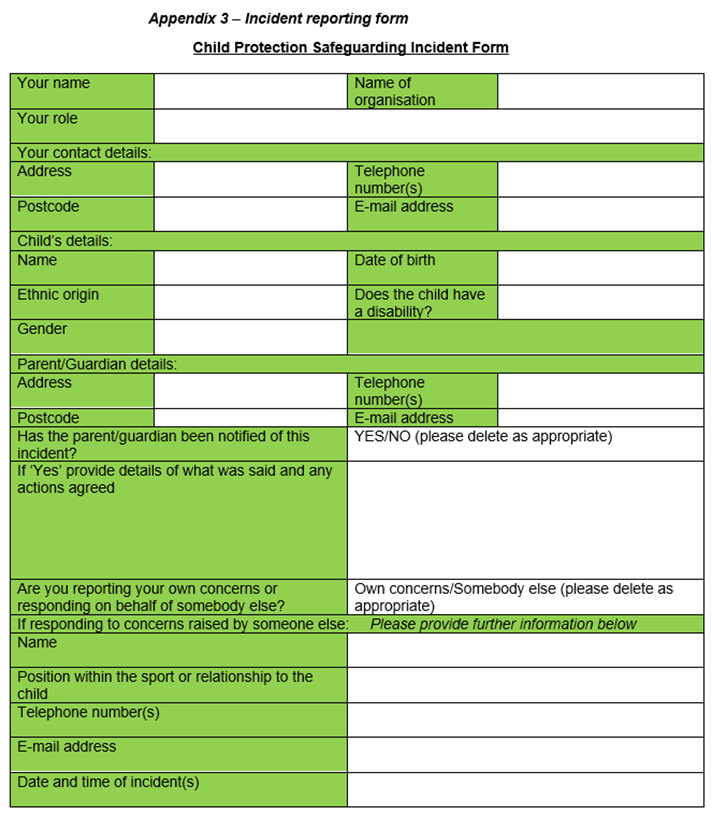

Appendix 3 - Incident Reporting Form

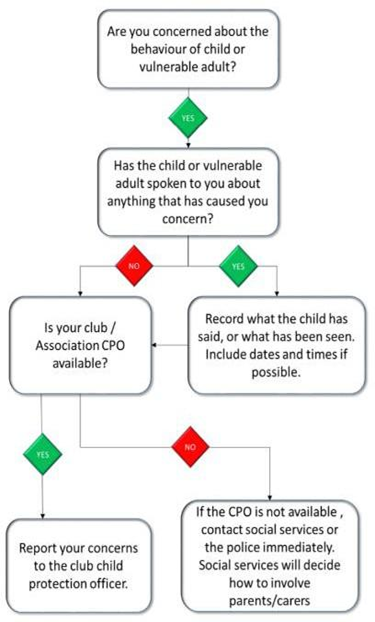

Appendix 4 - Child Safety And Welfare Concern Flowchart 1

Flow chart of action to take if there are concerns about a child’s safety or welfare. The following action should be taken if there are concerns:

The Child Protection Officer should always inform SHOTO’s Chair and Deputy Chair on the appropriate form within 24 hours of receiving a concern.

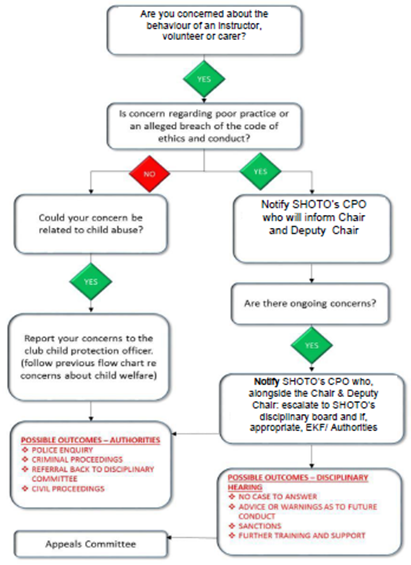

Appendix 5 - Child Safety And Welfare Concern Flowchart 2

Flow chart of action to take if there are concerns about instructors’, volunteers’ or carers’ conduct. The following action should be taken if there are concerns (continued):

Appendix 6 - Job Description For Association Child Protection Officers

Job Description For Association Child Protection Officers

About The Role:

The person within a karate organisation or club with primary responsibility for managing and reporting concerns about children and for putting into place procedures to safeguard children in the club in accordance with SHOTO policy.

Job Description:

- Work collaboratively with others to promote a positive child-centred environment.

- Assist in ensuring the Association/club meets its requirements to the EKF/SHOTO.

- Act as a point of contact for instructors, volunteers parents and athletes to raise concerns.

- Liaise with the SHOTO Council and other relevant bodies e.g. police and local authority when concerns are raised.

- Keep detailed records of concerns raised ensuring these are stored securely.

- Maintain confidentiality.

Person Specification:

- DBS checked or willingness to undertake.

- Understanding of child protection and safeguarding and the difference between the two.

- Basic knowledge of the roles and responsibilities of statutory agencies (children’s social care, the police and the NSPCC).

- Commitment to the cause of safeguarding.

- Basic administration and computer skills.

- Ability to communicate effectively with members.

- Knowledge of key contacts and where to signpost concerned parties.

- Boundaries to the role – recognition that this is not an investigatory role.

N.B. Training will be provided by the EKF for Association Child Protection Officers.

Appendix 7 - Parental Consent Form - Photography

Parental Consent Form For The Use Of Photography Of Children And Young Persons

Children and young persons are photographed in connection with SHOTO:

- Instructing and training aids.

- Advertising, Publicity and Promotional works.

Parental photography forms an enduring part of each family’s record of their child’s progress, celebration of success and achievement, as well as being an established social practice.

We may require on a per event basis your permission for photography to be taken. ‘Photography’ includes photographic prints and transparencies, video, film and digital imaging. ‘Events’ means any function, meeting, training session or competition of any nature, whether organised or supported or sponsored by English Karate or their Association members by any means whatsoever, wherever children or young people are the responsibility of English Karate Federation, their members or their Associations instructors, volunteers or members.

I give / do not give (delete as appropriate) permission for photography of my child to be taken by authorised personnel for or on behalf of SHOTO.

Child's name:

Signed (parent / guardian):

Date:

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………